Remember a month or so ago when I wrote a post stating that documentation from the 1740s, particularly the presentments and indictments, was getting a bit iffy? Presentments weren’t there when they should have been, material from decades earlier or later had been chucked in at some point in the past seemingly at random, and I speculated that somewhere there’d probably been a huge mix up with the documents and that perhaps some poor clerk had dropped a huge file of material on the floor?

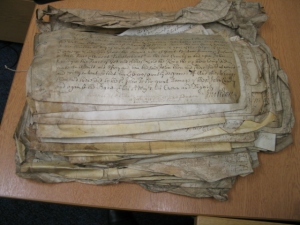

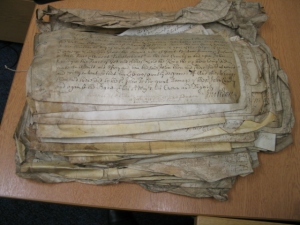

Well it seems the clerks of three hundred years ago may have got just as puzzled as I did with it all and in the end they seem to have given up completely and left a mystery file with the Michaelmas 1747 Sessions bundle. Ladies and gentleman, I give you….THIS:

This is what is rather hopefully termed a ‘process file’, found in the Michaelmas 1747 box. The rear of the file has a wrapper with a somewhat cyptic inscription: ‘process file, home to ye pardon, M[ichaelmas] 1747.’ Indictments are present in the file ranging in date from Michaelmas 1747 back to 1723 (possibly earlier, I’m yet to catalogue it). Although loosely sorted into chronological order, the emphasis there is on the word ‘loosely’. There are 160 documents in this stack of parchment alone (just to put that into perspective, an average 18th-century Devon Quarter Sessions bundle has around 180 documents altogether!) and each of them has clearly been removed at some point from its original bundle (because many of them are marked with a former numbering system that doesn’t correlate to the documents around them) and slung together in one great mass of material.

A number of the 1740s bundles have seemed a little bit lacking in presentments and indictments given the amount of business attested to be before the court by the recognisances, and I wouldn’t be at all surprised if a large amount of that material has ended up here. There are also some notable cases that dropped off the radar that I’d assumed had ended up being tried before the Assizes (the records for which are in the Western Circuit papers at Kew). We never found out what happened to the wreckers of the Dutch Ship, for example. Were they dealt with by the Quarter Sessions after all, and are their presentments and indictments in here?

No doubt this file will answer a lot of questions but it’ll also pose many new ones, chief among them being, why did the indictments never get placed back with their original material? Clearly there was a purpose to pulling all of this material out, and it seems that in many cases referred to in this file, defedants appeared many years after the original indictment was made, and submitted to justice, indicating that perhaps this file was originally for ‘open’ cases that had yet to be concluded. However, defendants appearing some time after originally indicted, often many years later, as is happening very often in this file, isn’t something that’s unique to this file. In fact, this happens all the time with presentments and indictments in the main Sessions bundles, and usually the indictment remains in the bundle relating to the date when the offence and trial were finally concluded.

For some reason then these indictments were all treated differently, and for some reason, in 1747, this ended. Did the clerks switch over to a new system of filing indictments treated in this way? And why, if they ended the file in Michaelmas 1747, did they not return the documents to their original contexts? Was it perhaps too much of a job? Or, did they start and then give up? I’ve been finding 1720s material in some of the 1740s bundles, seemingly at random, and perhaps this is evidence of the clerks attempting to return some of this material to where they thought it belonged. Perhaps, in the end, the clerks decided it’d be best to leave the file along with the Sessions bundle which related to the latest material contained within it, and start a new file. It seems odd though that they didn’t decide to keep this process file separately to the Sessions bundles, since there was clearly, at some point, a logic to separating this material out from them.

All in all, the reasons as to why this file of material ended up in the Michaelmas 1747 Sessions bundle box are puzzling. The material contained in this file spans well over two decades of legal material, however, and returning all of the indictments to their original bundles would certainly have been a formidable task. For whatever reason the file was left in the Michaelmas 1747 box, waiting to be discovered, and now comes the challenge of cataloguing it.

Cataloguing this material is going to be a very painstaking business. All records will have to be cross-referenced as far as possible, and for each session for which out of sequence material survives in this bundle, notes will have to be made and placed within the boxes on the shelves in the strong room going back as far as the 1720s to ensure that future researchers are made aware that material pertinent to their research survives, of all places, in the Michaelmas 1747 box.

I’ve catalogued around 10,000 documents now and this discovery underlines another important point: no matter how much experience you gain with this material there’ll always be something new and unexpected to discover. And in the end, that’s what makes a job like this such good fun, really!