A while ago I made a passing remark in a blog post about the way that working with a collection extensively brings you to appreciate it in sometimes very weird and wonderful ways. I often find myself wondering, for example, what John Fortescue’s life was like, and trying to picture the office in which he worked originally with so much of the documentation I’m now cataloguing. But there are a great many other things that strike you when you’re working with a collection like this daily that might not seem strange or out of the ordinary to someone taking a casual look at the documents in the search room, so I thought I’d write about a few examples, because they give us the chance to make interesting deductions about the records.

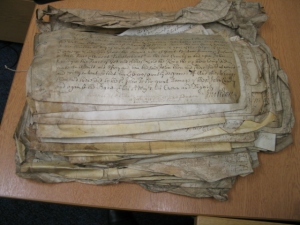

Take, for example, the way in which the documents are originally received. Usually, each bundle is rolled up inside its wrapper, with the presentments and recognisances nesting within, and, more often than not, a stack of documents outside the roll that varies in date and contains all manner of material (this is the material I’ve got volunteers sorting and organising by date, session and document type). This is the way almost all the rolls have been found, and after they’ve been conserved and catalogued, everything’s flattened out and we have the normal finished product.

The documents for Midsummer and Michaelmas 1743, however, have been somewhat different. Rather than appearing inside their rolls, the presentments and recognisances, (which always come in batches, tied together onto a spindle at the side of the document with string), have been individually rolled, and placed in the box.

Separately, from 1742, there’s been a little oddity with the presentments, too. Presentments usually have a number of dates on them; there’s one on the left hand side which indicates when the offence being tried took place; rendered as ‘Epiph 1741’ for example. Often, there’s also then a series of annotated dates on the bottom of the document, such as ‘Apr. 19 1742, defendant appears and pleads not guilty’ and then ‘October 12 1742, defendant withdraws plea, submits, and is fined.’ Bear in mind that presentments aren’t always annotated at the bottom, but in the hypothetical example here, we’re assuming it has been. This gets a bit involved, so bear with me.

There’s a logical sequence of events depicted in the dates on the document. The offence happens in Epiphany 1741 (which, accounting for pre-1755 dating rules, means circa January 1742, as we would understand it today). The hypothetical document therefore has a date saying ‘Epiph 1741’ on the left hand side. With me so far? The next available sessions to *try* an offence taking place in January 1742, when Epiphany sessions would *already* have been sitting, would have been Easter 1742. The offence is therefore first presented in Easter 1742, which might’ve sat in April, say, for the sake of argument. This is where the first annotation at the bottom of the document, about the defendant pleading not guilty, comes in. The defendant eventually, however, later in the year, withdraws his not guilty plea, and is therefore fined, at the Michaelmas session for the year 1742. This gives us the ‘Oct 1742, defedant withdraws plea…’ etc etc annotation. This final annotated date, giving the date a verdict or conclusion to the case was reached, normally corresponds with the date of the sessions bundle the presentment has been found in, ie all the presentments in the Michaelmas 1742 bundle that have been annotated like this will have a little note saying what happened at the Michaelmas 1742 session. Logically then, in other words, these dates noting when an offence was tried and punished, should correlate with the surrounding material.

Since 1742, however, there have been examples of them not doing.

Take for example QS/4/1743/Michaelmas/PR/25. Felix Phillips of Silverton is being presented for breaking and entering the house of Thomas Channon and committing an assault and battery on Thomas, and Susannah, Thomas’ wife. The offence date (on the left hand side) marks that this occurred in 1737. That in itself isn’t a problem; it’s fairly common for offences to be tried long after they took place, so that in itself isn’t odd on its own. What is odd is the annotation ‘Mids. 1740 def appears, submits and is fined.’ The offence, in other words, has already been tried and concluded several years previously. So why is the presentment for the case filed on the same spindle as a group of presentments from Michaelmas 1743? This is as we’ve found them, remember, and this is by no means an isolated case; there are a good number of similar documents emerging, with the dates of the conclusions to the cases usually several years out from the session they’ve ended up being filed with. So in other words, I know from the interior logic of the documents, that at some point several hundred years before we opened the boxes here in Exeter to catalogue them, they’ve ended up getting interspersed and bound together with other material.

Finally, when I first started out cataloguing this material, there was no specific reference to ‘Easter 1743’ on any of the boxes, leading me to wonder whether there’d been a session held for Easter at all. Logically though, I found that there must’ve been, because loose documentation for highway repairs was turning up, so a court of some kind must’ve sat, and there was no documentation suggesting anything unusual going on before Easter 1743, like a major smallpox epidemic which might’ve caused the justices to postpone the sessions. So where were all the presentments and indictments, the recognisances, and the like? In the end, they emerged interspersed with the Epiphany 1743 material, where they’ve been for 300 years before we opened the boxes.

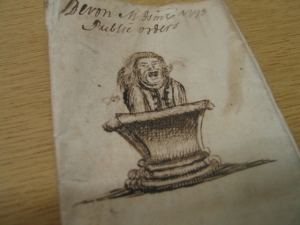

So what can we deduce from all this? Well, although we’re unlikely to find a document from an errant clerk of the peace saying ‘good grief, I seem to have dropped about 300 presentments on the floor and I’m not sure where to file them again’ it seems obvious that at some point in the last 300 years since the records were made, there was some kind of accident with some of the material from 1742 onwards which led to documentation being disordered and interspersed with material for other years. The fact that the Midsummer and Michaelmas 1743 material was found with its component documents individually rolled up suggests that someone other than the usual clerks handled this material at some point in the past, though we can’t be sure who this might have been, or when this took place. Our conservators believe that from the kind of dirt and the distribution of dirt on the documents, the records must’ve been stored at some point in a room in which a coal fire was in use, a tantalising detail.

Bringing all of this together, much of this underpins the underlying purpose of cataloguing; to bring order to material that has lain in disorder perhaps for centuries, and the process of doing this throws up anomalies like these from time to time. Because I’m working with this material day to day, I’m seeing these small oddities in a different light to that that most researchers in future will see them in, and together these small quirks build up a bigger picture. This is part of the fun of the job.

I currently don’t know the extent of the disorder in the presentments, which will become clearer as I catalogue further, though I suspect that it’ll only affect material over a relatively small range of dates. I’ve been keeping a log of it since it first became apparent about a month ago, and it’ll be interesting to see whether further evidence emerges from the collection which might explain why it occurred in the first place, though I suspect we’ll probably never know for sure. But it’s certainly intriguing and all part of the fun of the job. If only John Fortescue were alive today, I could ask him about it in person….but that’s the way it goes, I guess. Have a great weekend folks!